Essential Reading

The most important sources for understanding the relation between topography and culture in New Orleans are:

Richard Campanella, Geographies of New Orleans: Urban Fabrics Before the Storm (Lafayette, Louisiana: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2006)

and its predecessor,

Pierce F. Lewis, New Orleans: the Making of an Urban Landscape, second edition (Santa Fe, New Mexico: The Center for American Places, 2003).

Day Labor Station

The Day Labor Station leverages design to advance the discussion about day laborers and their role within the fabric of the community. The prototypical structure can be deployed at informal day labor locations. The design is based on the realities of the day labor system and responds to the needs and desires of day laborers themselves, as clients. Public Architecture is working to locate a permanent site for the first Station. Ultimately, Day Labor Stations will be deployed across the country. See more at www.daylaborstation.org.

The Day Labor Station leverages design to advance the discussion about day laborers and their role within the fabric of the community. The prototypical structure can be deployed at informal day labor locations. The design is based on the realities of the day labor system and responds to the needs and desires of day laborers themselves, as clients. Public Architecture is working to locate a permanent site for the first Station. Ultimately, Day Labor Stations will be deployed across the country. See more at www.daylaborstation.org.

Scrap House

ScrapHouse was a temporary demonstration home, built entirely of salvaged material on Civic Center Plaza adjacent to San Francisco City Hall. It demonstrated the possibilities – as well as the challenges – of green building, recycling, and reuse. Public Architecture is also working on resources to foster greater integration of material reuse within the building industry.

ScrapHouse was a temporary demonstration home, built entirely of salvaged material on Civic Center Plaza adjacent to San Francisco City Hall. It demonstrated the possibilities – as well as the challenges – of green building, recycling, and reuse. Public Architecture is also working on resources to foster greater integration of material reuse within the building industry.

Established in 2002, Public Architecture identifies and solves practical problems of human interaction in the built environment and acts as a catalyst for public discourse through education, advocacy, and the design of public spaces and amenities. Supported by the generosity of foundation, corporate, and individuals grants and donations, Public Architecture works outside the economic constraints of conventional architectural practice, providing a venue where architects can work for the public good.

Norris Dam

Norris Dam, named after Senator George Norris of Nebraska, the original sponsor of the TVA legislation, was the first of the TVA dams to be completed. Internationally renowned architect Le Corbusier visited Norris in 1946 and, according to his protege Paffard Keatinge-Clay, returned to his Paris studio to declare that he had seen some wonderful concrete work in Tennessee, which he was going to emulate and name beton brut.

Norris Dam, named after Senator George Norris of Nebraska, the original sponsor of the TVA legislation, was the first of the TVA dams to be completed. Internationally renowned architect Le Corbusier visited Norris in 1946 and, according to his protege Paffard Keatinge-Clay, returned to his Paris studio to declare that he had seen some wonderful concrete work in Tennessee, which he was going to emulate and name beton brut.

Generator Housings, Pickwick Dam

Visitors Lobby, Kentucky Dam

Each TVA project included visitors centers, like this viewing room at Kentucky Dam, designed to educate the public about the operation of the facility. At each facility, the dates of construction are given, along with the motto, “Built for the People of the United States.”

Each TVA project included visitors centers, like this viewing room at Kentucky Dam, designed to educate the public about the operation of the facility. At each facility, the dates of construction are given, along with the motto, “Built for the People of the United States.”

John Peterson

1% Solution

Public Architecture

Architect John Peterson is a recognized expert on zoning and entitlement issues and public review processes. Honored for his work with the San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Community Development Non-Profit Task Force, he is a board member of South of Market Business Association and of Urban Solutions, a business development non-profit. The Founder and Chairman of Public Architecture, a non-profit, public interest architecture group, he was a 2005-06 Loeb Fellow at Harvard University.

Support New Orleans with your ears

Memory & Anticipation

The formality of Jackson Square—its symmetry and the cathedral’s frontality—doesn’t jive with our everyday experience of it. We don’t march up to the square on axis, but instead come from the side, along Chartres Street, walking from the streetcar and bus stops along Canal or Esplanade. But the order of the square is in our minds, anyhow.

The formality of Jackson Square—its symmetry and the cathedral’s frontality—doesn’t jive with our everyday experience of it. We don’t march up to the square on axis, but instead come from the side, along Chartres Street, walking from the streetcar and bus stops along Canal or Esplanade. But the order of the square is in our minds, anyhow.

The symmetry of the cathedral’s façade, obliquely viewed and opening onto light, suggests the presence of the square before the square itself is seen and lures us with a foretaste of arrival. Memory and anticipation accompany us in our experience of the city, the seen, the remembered, and the imagined, all intertwined.

In Then Up Then Out Again

All the world’s a stage, but especially the balconies. Imagine it’s Mardi Gras day, and you are on St Charles Avenue, along the route of the Rex parade. Behind you and overhead, you hear laughter and loud talking, a party on the balcony of a house. One thing leads to another and pretty soon someone lets you in and brings you up a dark, curving stair, and you’re on the balcony yourself. All of a sudden you’re big friends and there’s plenty of beer and boiled shrimp.

All the world’s a stage, but especially the balconies. Imagine it’s Mardi Gras day, and you are on St Charles Avenue, along the route of the Rex parade. Behind you and overhead, you hear laughter and loud talking, a party on the balcony of a house. One thing leads to another and pretty soon someone lets you in and brings you up a dark, curving stair, and you’re on the balcony yourself. All of a sudden you’re big friends and there’s plenty of beer and boiled shrimp.

Physically, you’ve ended up not so far from where you began, but the social gain is dramatic. Along with the beer and shrimp you get gossip about the Rex krewe and whichever Louisiana politician is (like the shrimp) in hot water today. And, while you’re still part of the audience, you’re now equally part of the show.

Knowledge and performance, initiation and display: these are no doubt terms of the social economy anywhere, but in few places are they dramatized like they are in New Orleans.

Depth & Appearance

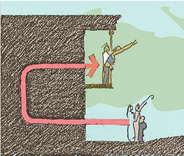

There must be some things about the spatial patterns of New Orleans that are different from the patterns of Chicago or Louisville or Sacramento. Preservation Hall demonstrates one such pattern: Standing outside the window, you look across the backs of the musicians to the audience, crowded into folding chairs and onto the floor of the simple space. For a few dollars, you can join the audience inside. You enter through a carriageway to the right of the storefront, pass down it to a door at the back of the room, turn, and sit facing the musicians—and, behind them, the window through which you had looked. You are “in.”

There must be some things about the spatial patterns of New Orleans that are different from the patterns of Chicago or Louisville or Sacramento. Preservation Hall demonstrates one such pattern: Standing outside the window, you look across the backs of the musicians to the audience, crowded into folding chairs and onto the floor of the simple space. For a few dollars, you can join the audience inside. You enter through a carriageway to the right of the storefront, pass down it to a door at the back of the room, turn, and sit facing the musicians—and, behind them, the window through which you had looked. You are “in.”

Looking in on a scene with its back to the front, seeing people like yourself beyond the scene looking back at you, finding your way into that scene through an extended passage with a final about-face, seeing the same scene from a privileged position: this scenario is characteristically New Orleanian.

Twist It, Baby

In New Orleans, the great geographical fact is the bending of the Mississippi River. Its curve causes the street grid to bend in fragments reflecting the subdivision of former plantations. The converging streets produce oddly shaped lots.

In New Orleans, the great geographical fact is the bending of the Mississippi River. Its curve causes the street grid to bend in fragments reflecting the subdivision of former plantations. The converging streets produce oddly shaped lots.

Wonders appear on the lots that are just big enough to build on: triangular buildings, trapezoidal buildings, and flatirons. Because people as well as geometries often converge at these intersections, commercial enterprises frequently thrive here.

Traditional forms melt into the embrace of the city, echoing the languid curve of the great river. Architects call buildings “sexy” when they catch the eye or show a bit of structural leg. Usually, it is a vague and meaningless term. But if buildings ever were sexy, these are: taut, form fitted, pressing up close to the street.

Multi-Functioning Buildings

In the corner store / residence, the floor of the commercial space is but a single step above the sidewalk. At the rear of the store—or restaurant or bar, where the kitchen may serve both business and residence—three more steps lead up to the dwelling.

In the corner store / residence, the floor of the commercial space is but a single step above the sidewalk. At the rear of the store—or restaurant or bar, where the kitchen may serve both business and residence—three more steps lead up to the dwelling.

Both store and house are contained by the single continuous box of the shotgun and held under the continuous gable roof, but a hierarchy of privacy is developed in the economy of the section. (This is the early “suburban”—or should that be “faubourgian”?—variation of the French Quarter’s Creole townhouse, where the residence is literally and directly above the commercial space.)

The Stoop & Social Space

In New Orleans, people know how to fancy-up for a public event. They know how to embrace visitors, as well. Buildings in New Orleans do these things, too. The front stoop of a shotgun house does. Its gingerbread ornament shapes and celebrates the place where the resident chats with passers-by.

In New Orleans, people know how to fancy-up for a public event. They know how to embrace visitors, as well. Buildings in New Orleans do these things, too. The front stoop of a shotgun house does. Its gingerbread ornament shapes and celebrates the place where the resident chats with passers-by.

So do the wrought iron galleries of the Quarter. In both cases, resources are spent where they matter: where they bring people together.

The River Roads

The earliest roads in New Orleans paralleled Bayou St John, Bayou Metaire, and Bayou Gentilly, whose banks had been raised above the surrounding swamps by the silt of periodic flooding. Settlement followed the high ground. Farms were established along the bayou roads, where cultivation was possible for a distance of three arpents, or roughly two-hundred yards, from the banks of the bayou. These routes — Bayou Road cutting diagonally across the grid along the route of the old Choctaw portage; Gentilly Boulevard, winding to the east; Metairie Road to the west; and Wisner Boulevard in City Park — remain the sensible lines of habitation between the river and the lake.

The earliest roads in New Orleans paralleled Bayou St John, Bayou Metaire, and Bayou Gentilly, whose banks had been raised above the surrounding swamps by the silt of periodic flooding. Settlement followed the high ground. Farms were established along the bayou roads, where cultivation was possible for a distance of three arpents, or roughly two-hundred yards, from the banks of the bayou. These routes — Bayou Road cutting diagonally across the grid along the route of the old Choctaw portage; Gentilly Boulevard, winding to the east; Metairie Road to the west; and Wisner Boulevard in City Park — remain the sensible lines of habitation between the river and the lake.